[Student IDEAS] by Michelle Diaz - Master in Management at ESSEC Business School

Very few things are as malleable and rule-stricken as language, composition, and rhetoric. In 2022 alone, Merriam-Webster added 370 new words to the English dictionary. But certain grammatical rules have been in place for centuries. Perhaps it is this contradictory, confounding, and ever-evolving nature of language that allows trained writers to still overwrite artificial intelligence (AI). However, a recent paper suggests that even writing-intensive professions are exposed to AI, with 80-100% of the US workforce affected (Eloundou et al., 2023).

But what does this mean for academia? Should academic institutions hurry to shift assessment standards, create safeguards, and implement fraud-detection measures? Most say yes; others insist it is a threat to education like no other, while some tout it as a wondrous opportunity. AI is all of this and more: a chance for a wider array of students to understand, appreciate, and learn the art of composition—to consider the skill as something they would like to possess. Rather than outsource to AI-powered chatbots, simply because they can.

The reaction to the release of ChatGPT, an AI-powered chatbot developed by Open AI has been wide-reaching. The reception can be found in almost every sector, from business to healthcare, law, and entertainment to name a few. But in no sector is the reception more mixed and controversial than that of academia, the common denominator of almost every sector. Every prospective CEO, health professional, lawyer, screenwriter, and professor must, in one way or another, prepare for their career through some level of education.

The bombardment of headlines ranged from the optimistic, “AI Could Be Great for College Essays” (Lametti, 2022), to a nuanced analysis, “The Brilliance and Weirdness of ChatGPT” (Roose, 2022), and the proactive response, “How to Use ChatGPT and Still Be a Good Person” (Chen, 2022). The timeline of these headlines was early in the launch of ChatGPT. But the headlines since the release of ChatGPT-3.5 and GPT-4 have in large part reflected the same flurry of mixed emotions, with “The Chatbots Are Here, and the Internet Industry Is in a Tizzy” (Mickle et al., 2023) and “‘Let 1,000 Flowers Bloom’: A.I. Funding Frenzy Escalates” (Griffith et al., 2023), and the op-ed of the esteemed father of modern linguistics, “Noam Chomsky: The False Promise of ChatGPT” (Chomsky et al., 2023).

Irrespective of the views on ChatGPT, one thing is clear: a paradigm shift is needed. The repercussions of ChatGPT’s very existence mean the technology will only get better given the historical rate of technological innovation and competition within the market. On March 21, 2023, Google launched its Bard chatbot, the tech giant’s bid to rival Open AI’s ChatGPT. While Baidu, the Chinese search giant, released their own chatbot, Ernie, earlier in March 2023, (Murgia, 2023). In essence, a proactive approach is required to handle the effect on academic integrity.

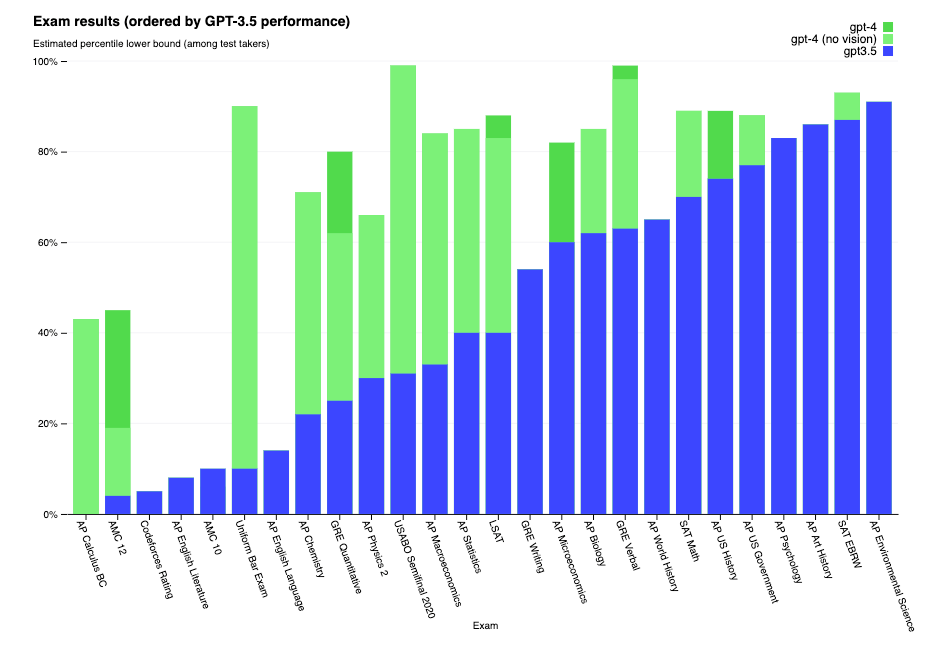

What exactly is academic integrity? And how do chatbots like ChatGPT, Bard, and Ernie threaten it? Moreover, how might we leverage these chatbots to improve education instead of sending teachers, schools, professors, and universities into a frenzy of concern over academic fraud? According to Donald McCabe, the founding father of research into ethical policy in academia, “the term involves the avoidance of plagiarism, cheating, and other behaviours of misconduct” (McCabe et al., 2016). The speed at which detective measures have sprouted is commensurate with the capacity of the technology. Indeed, the benchmarks done by Open AI for GPT-4 reveal that the model can perform exceedingly well in a simulation of exams originally designed for humans:

Hence, it comes as no surprise that, not three months since ChatGPT’s release, Edward Tian, an undergraduate student at Princeton University, created GPTZero, a bot to detect a text written by ChatGPT (Bowman, 2023). Similarly, Eric Mitchell, a graduate student at Stanford University, is working on DetectGPT, yet another means to distinguish between human and large language model (LLM)-generated text (Mitchell et al., 2023).

In effect, many of the metrics that society at large measures academic performance can be gamed by AI. Like essay assessments that require no oversight at the time of writing. But there has always been a case to mitigate academic misconduct, even before AI: “In the past, students could hire a ghost writer through widely available and easily accessible essay mills to write an assignment. Now with ChatGPT, they can instruct artificial intelligence (AI) instead of a person, at no cost…” (Harte et al, 2023). The qualifying difference is the ease with which students may now cheat.

Interestingly, the one area in which GPT-4 has performed less admirably is the skill of writing. It showed no significant improvement from the last two versions for AP English Language, Literature, and the writing portion of the GRE (Open AI, 2023). Consequently, one must distinguish between subjects wherein equal weight is put on a text’s content and the quality of the writing itself. One can argue that assessment standards should be modified to require the high clarity, concision, and eloquence that is often demanded of students studying subjects like creative writing, literature, or philosophy. Or else, the mode of assessment be modified, or a reliable means of detecting AI-written text made widely available.

In early 2023, The New York Times published an article wherein more than 30 professors, students, and university administrators were interviewed on how to adopt to ChatGPT. Together, they outlined three ways to address the issue: require a higher standard of writing, modify assessment, and create a detector for AI-written text. One professor claimed that the “imagination, creativity, and innovation of analysis that we usually deem an A paper needs to be trickling down into the B-range papers.” Another professor now requires students to write their first drafts in the classroom. Lastly, the article underlines how more than 6,000 professors from Harvard University, among other tertiary institutions, have signed up for Edward Tian’s GPTZero (Huang, 2023).

In any case, one thing is clear: the real conundrum is the ease with which students will willingly use ChatGPT for their academic assessments. Indeed, therein lies the potential of AI to either be beneficial or detrimental. If a student can save time, effort, and learn better with ChatGPT, then academia is better served by ensuring that students are more inclined to use it without forgoing academic integrity; to act based on an intrinsic preservation of integrity, rather than the avoidance of negative extrinsic repercussions of misconduct. And certainly, the uses of AI to improve academic practice are abundant, from providing a personalized learning experience to helping students brainstorm ideas to curating relevant resources (Hamdan, 2023).

Considering the dilemmas ChatGPT raises about academic integrity, it is prime time to refocus on a core issue that predates AI: the perception on the necessity of learning to write well. In 2002, Petelin coined the terms, “working writers and writing worker to distinguish between professionally trained writers (career writers) and those who are not necessarily trained as professional writers but whose jobs require them to write.” The former refers to journalists, playwrights, poets, etc. While the latter refers to lawyers, managers, engineers, architects, etc. (Petelin, 2022). The perception is that certain occupations require less training in writing, and indeed, not every individual must aim to write to the degree that career writers do. After all, a medical student is better prepared by spending more time on the sciences.

However, instilling students with the desire to learn writing beyond the requisite level to pass their courses is an investment that is unquestionably worthwhile. As Oscar Wilde once said, “If you cannot write well, you cannot think well; if you cannot think well, others will do your thinking for you.” Likewise, Joan Didion, a celebrated American writer mirrored this sentiment: “Had I been blessed with even limited access to my own mind, there would have been no reason to write.” While Stephen King notes that “writing is refined thinking” (King, 2000). These writers, whether they knew it at the time or not, were talking about the writing-thinking-learning connection, a relationship that language scholars have long since studied. Essentially, writing about something allows one to understand and learn it better, thus exploiting the connection between the three acts (Petelin, 2022).

Moreover, research shows a high correlation between writing and speaking. A study done in 2022 revealed that “student achievement in learning writing skills can predict achievement in learning speaking skills, and vice versa. If a student has good writing skills, it is almost certain that he will have good speaking skills as well” (Rahman et al, 2022). And speaking well is indubitably beneficial across different careers. Furthermore, a meta-analysis on the effects of writing on learning in science, social studies, and mathematics concluded that teachers in these subjects “can reasonably expect that asking their students to write about content material will enhance learning” (Graham et al, 2020). Not to mention the capacity of writing to be therapeutic and beneficial for mental health (Bergqvist et al, 2020). Value is found in the act of writing itself, exclusive of the output produced; value that is forgone by heavily relying on AI.

To effectively capitalize on AI while preserving academic integrity, intervention can be divided into two categories: changing academic practices and student attitudes toward the importance of writing well. For the former, we have the tactics outlined by professors, like modifying assessments and creating GPTZero. While the latter category requires a stronger push. But combined, the two interventions provide intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and are thus a better way forward for students and academic institutions alike.

But what does changing student attitudes toward writing well look like? As it stands, the way that we teach students to write differs too much across disciplines, and some students inherently find the act of writing cumbersome. Instead of an enjoyable, empowering, and powerful skill for any career – “Its importance in organisations often goes unnoticed until there’s a document-related crisis” (Petelin, 2022). Furthermore, in most “Australian and British universities, writing is under-taught, under-valued, and under-researched” (Petelin, 2022). In contrast to American universities, where there is a long and strong tradition of rhetoric at the undergraduate level (Petelin, 2022).

Good rhetoric and composition speak for themselves. Often, the challenge is exposure to quality writing that inspires; to strings of words that entice not only with their content but with an eloquence that arrests. Sentences that speak not only about desire, but is desire embodied—obsessively, incessantly, and with a maddening hunger whose tendrils worm their way into a reader’s mind. No. The kind of writing found in required texts for subjects outside of the arts and humanities is far too often dry. Texts that read more like an instruction manual than anything else. How often do people read the instruction manual? Only when the table, despite all the tinkering, cannot be trusted to hold itself together. Now, perhaps the last couple of sentences sparked in you a defiance, a sort of stubbornness that proclaims: I always read the instruction manual! Or, most plausibly: not all writing needs to be creative writing! Indeed. I concur.

But all writing can benefit from amelioration. At the time of Dr. King’s illustrious I Have a Dream speech, he was scarcely the only man who dreamt of the “unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all men” (King, 1963). But he was one of the most eloquent. And while eloquence by itself does not a great leader make, it is a common denominator. From Dr. King to former president Barack Obama and to Professor Richard Feynman, notable not only for his contribution to physics but also for his ability to teach well.

Ergo, a solution might be to initiate introductory classes on literature and composition for academic departments like the hard sciences, healthcare, and business; make the skill more accessible. In this way, students learn early the supremacy of good writing, heightening the likelihood that they willingly invest time in the craft. Despite the presence of technologies that can write for them. Or else, more universities could adopt the practice of many American universities, where students must take classes on rhetoric and composition. Regardless of their chosen major (Petelin, 2022). If done correctly, swiftly, and universally, AI may very well bring about a resurgence in the art of rhetoric and composition—to the benefit of society at large.